Technical Analysis: Anti-Drone Radar ATR Technology - Chapter Three

Release time:

2024-12-04

3 ATR

Radar requires specific technology for target recognition. ATR technology is defined as a process that utilizes information obtained from radar, through signal processing and information interpretation methods, to acquire detailed information about the physical characteristics, scattering characteristics, etc., of the target, and ultimately determine the target attributes.

Target recognition is the core step of radar signal processing, but it is also a key aspect often overlooked in traditional radar engineering. "Detection" is defined as a process that includes two steps: first is signal detection (signal extraction), using basic threshold detection principles; second is echo recognition, which requires answering the question of what target the threshold-exceeding echo represents. Therefore, radar detection is the process from "signal detection" to "echo recognition." ATR technology is widely regarded as a cutting-edge technology in the field of radar. Due to its sensitivity, many technical details about ATR are not publicly disclosed. However, referring to Table 1, it can be seen that many anti-drone radar solutions possess target recognition capabilities.

3.1 Target Characteristics

In terms of detecting targets with anti-drone radar, small drones have unique characteristics, including a low radar cross-section (Radar Cross Section, RCS), slow speed, and low flight altitude; therefore, these drones are also referred to as LSS targets. However, a quantitative reference is still needed to describe the types of drones; otherwise, it is difficult to guide the design of anti-drone radar. In 2008, relevant Chinese authorities proposed the concept of LSS radar targets to describe small aerial objects with typical RCS values below 2 m², flight speeds below 200 km/h, and operating at altitudes below 1000 m.

At the same time, the classification standards for drones designated by the U.S. Department of Defense can also be referenced, namely Group 1 & 2 drones, as shown in Table 2. Group 1 & 2 drones typically have a radar cross-section range of 0.01 to 0.1 m², with sizes approximately 1/10,000 to 1/1,000 that of a typical aircraft (as shown in Figure 4). Group 1 & 2 drones are usually lightweight, compact, and used for short-range reconnaissance and surveillance tasks. Additionally, they have wide applications in the civilian sector, such as aerial photography, mapping, and inspection. These remotely controlled drones can carry various sensors, cameras, and payloads to collect data and complete specific tasks. Overall, Group 1 & 2 drones play an important role in contemporary military and civilian applications, providing an economical and versatile platform for various applications, and are the main detection targets for anti-drone radar.

3.2 Recognition Methods

In 1958, Professor Barton from the United States successfully identified the corner reflector structure on the Soviet Spark-II using radar echo signal analysis, marking the beginning of radar ATR technology. Generally speaking, the radar ATR function is usually regarded as an additional module integrated into existing radar systems, which means that the ATR module must operate within the constraints imposed by radar parameters. Notably, Peter Tait, a scholar from the British company BAE, authored a book covering the basic principles of radar ATR solutions, detailing this subject. Similarly, David Blacknell and Hugh Griffiths co-authored a comprehensive book on radar ATR, exploring various aspects of ground targets, aerial targets, and maritime targets. Over the past few decades, multiple ATR schools have recognized the importance of radar characteristics necessary for successful ATR applications in specific situations. Radar ATR technology can be classified into several schools based on characteristics, including RCS, high-resolution range profiles (HRRP), multi-polarization, micro-Doppler, and trajectory discrimination.

Regarding the application of anti-drone radar, it is worth noting that there are challenges in detecting and recognizing small drones using HRRP, as sub-centimeter level range resolution is required to capture the structure of drone targets smaller than 1 m. This requires radar transmission bandwidth in the GHz range, which traditional anti-drone radars find difficult to meet. Common anti-drone radars use narrowband, low range resolution, forcing RCS characteristics, micro-Doppler, and kinematic features to become one of the main options for recognition.

Theoretically, the inherent frequency of a target is a function determined by its shape and material composition, and since the inherent frequency is not affected by distance and altitude, it has the characteristic of enhancing target recognition robustness. Assuming the radar transmission is Shv = Svh, the target's backscattering matrix S can be expressed as:

The statistical distribution of the scattering matrix presents certain target information, but it is important to note that using this method requires a basic understanding of the scattering polarization theory in the resonance region of the "pole" theory. However, extracting the inherent frequency and associating it with a specific object is challenging. Currently, practical radars on the market that employ this method are very rare. Due to the lack of clarity in the scattering mechanism of the resonance region, most research on this topic remains at the laboratory stage. Multi-polarization may be more commonly applicable to dense cluster-type targets, such as flocks of birds, clouds, rain, and foil strips.

The statistical characteristics of the target's RCS are one of the common classification features. RCS measures the scattering capability of the target, and the expression for σ is:

Where: r is the distance, Es is the scattering field, and Ei is the incident field. Therefore, RCS is a statistical average. For example, a jet typically has an RCS of about 100 m², while a small quadcopter drone has an RCS of about 0.1 m². The measured RCS of a target fluctuates over time, frequency band, and target posture, and can be represented as a waveform or time series. Additionally, the statistical characteristics of the target's RCS can provide valuable information about the target, such as size and shape, aiding in target recognition.

Another category of features is kinematic features, including speed and trajectory. Considering the target's speed as Vb, this is determined through Doppler measurements in the radar system. The Doppler frequency shift can be expressed as:

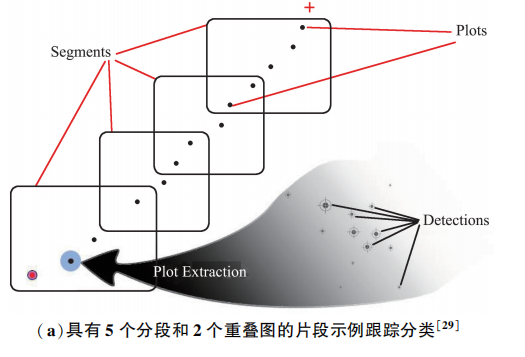

Where: D(r,t) represents general kinematic features, R represents the detection distance of the target, and r represents the radar's range resolution. These features are also known as trajectory classification, which has long been used in radar systems, especially for classifying aerial targets. When the radar system detects an aerial target, a trajectory is generated that records the target's movement over time. By analyzing these trajectories with trajectory classification algorithms, various target features can be determined, including size, speed, and flight patterns. This information plays an important role in target classification, theoretically capable of distinguishing between drones, airplanes, helicopters, or other types of aerial targets. However, several factors need to be considered when utilizing kinematic features. First, successful target detection is crucial for extracting kinematic features. Since drones typically emit weaker radar signals, the detection probability significantly affects the performance of trajectory classification, and there are interferences from other sources, such as birds, whose trajectory patterns are similar to those of drones, posing additional challenges for ATR performance. Furthermore, trajectory discrimination requires longer processing times and has a shorter recognition range, as kinematic features are not robust.

The micro-Doppler effect refers to the additional Doppler frequency shift caused by the small movements exhibited by a target, such as the rotation of helicopter blades or the flapping of bird wings. Assuming the speed of the drone is Vb, the micro-Doppler frequency shift can be approximated by considering the radial component of the blade speed in the radar line of sight. The relationship can be expressed as:

Where: R is the radar distance, L is the blade length, ω is the blade rotation rate, α is the azimuth angle, and β is the pitch angle. According to the above formula, the micro-Doppler frequency shift is modulated by two sine functions. Therefore, a comprehensive description of micro-Doppler features includes the modulation function, which essentially depends on the observation time. Micro-Doppler analysis can extract micro-structural information, which can be used for target recognition. Although micro-Doppler features are typically regarded as kinematic features, in this case, some specific micro-Doppler features are considered structural/geometric features.

Dr. Chen, the father of micro-Doppler theory, pointed out that the key challenge faced by the micro-Doppler method is the effective interpretation of extracted features and their correlation with target structural aspects. In the case of drone micro-Doppler, the micro-Doppler phenomenon mainly arises from the consistent rotational motion of the blades or the presence of rotating structures, as shown in Figure 5(b). This typical phenomenon allows for the extraction of unique radar features related to drones, such as the number of blades and rotation rate, greatly facilitating the identification of drones. Therefore, as shown in Table 1, many anti-drone radars utilize micro-Doppler analysis to identify drone signals.

Despite the advantages of micro-Doppler classification, it also faces some challenges. First, micro-Doppler is more of a phenomenon than a feature. The three forms of the micro-Doppler phenomenon (as shown in Figure 6) include: Jet Engine Modulation (JEM) or Helicopter Engine Rotor Modulation (HERM) modulation lines in the spectrum, the spectrogram of the 'blade flash' pattern obtained through Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), and the range-micro-Doppler image. The JEM spectrum refers to spectral peaks in the frequency spectrum with certain adjacent intervals and similar amplitudes, while the blade flash pattern describes the sine traces of micro-Doppler frequency on the spectrogram; secondly, enhancing the micro-Doppler signal comes at a cost, and not all radar dwell times are suitable for detecting micro-Doppler signals generated by rotating blades in drone radar signals. The radar dwell time cannot be too long or too short to effectively detect micro-Doppler signals. At the same time, a sufficiently high sampling frequency is required to obtain enough micro-Doppler information to separate the micro-Doppler signals. Insufficient micro-Doppler data may lead to incorrect estimates of the number of blades. Additionally, obtaining a high Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) for micro-Doppler images using machine learning algorithms is crucial for accurately identifying drones. Overall, the micro-Doppler method for identifying drone echoes is challenging.

3.3 Recognition Levels

For an ATR system or an ATR method, the ATR recognition performance first requires quantifiable metrics for constraints. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) provides a comprehensive framework for understanding ATR and assessing target attributes. Target acquisition is defined as the process involving the detection, identification, and precise localization of targets, aimed at effective weapon utilization. In contrast, recognition involves determining the nature, category, type, and, where feasible, subcategory of the detected personnel, objects, or phenomena. According to the NATO AAP-6 terminology and definitions glossary, the term 'Recognition' has a more specific meaning. This process can be imagined as a classification tree, in which targets are systematically classified into progressively refined subcategories, including:

① Detection: Separating the target from other objects in the scene.

② Classification: Assigning a meta-category to the target, such as an aircraft or wheeled vehicle.

③ Recognition: Determining the category of the target, such as a fighter jet or truck.

④ Identification: Specifying the subcategory of the target, such as a MiG-29 fighter jet or T-72 tank.

⑤ Characterization: Considering subcategory variants, such as a MiG-29 PL with fuel tanks or a T-72 tank without fuel tanks.

⑥ Fingerprinting: Conducting more precise technical analysis, such as a MiG-29 PL with reconnaissance pods.

It must be acknowledged that the boundaries between these decomposition steps may not be universally strict for all issues and targets. However, in existing research, there is often inaccuracy in the hierarchical division of ATR performance, and sometimes the terms 'classification' and 'recognition' are informally misused in discussions. This lack of clarity may lead to confusion regarding the effectiveness of radar ATR solutions. Furthermore, relying solely on a single radar capability may not achieve higher-level functions, such as 'Fingerprinting'. Therefore, in response to the demand for anti-drone radar, it is proposed to revise NATO's recognition hierarchy for radar ATR technology, where the performance of target discrimination based solely on this single sensor is as follows:

① Detection: Extracting radar signals of targets in the scene.

② Classification: Assigning a meta-category to the target, such as a drone or bird.

③ Identification: Determining the subcategory of the target, such as a fixed-wing drone or quadcopter.

④ Description: Conducting more precise technical analysis, such as a quadcopter drone DJI Phantom 4 with a Go-Pro camera payload.

4 Analysis and Discussion

Although few anti-drone radar manufacturers publicly acknowledge it, ATR technology has, to some extent, guided the design schemes of anti-drone radars. This section studies the typical design ideas of anti-drone radars in Table 1 from the ATR perspective.

To some extent, the performance of anti-drone radars directly affects the overall effectiveness of C-UAS, as it is responsible for executing early detection warnings and target location guidance tasks. The Gamekeeper radar from the UK company AVEILLANT and the SQUIRE radar from the French company Thales are chosen as typical representatives for comparison. In this paper, based on different ATR method perspectives, the former is referred to as 'track radar' and 'micro-Doppler radar'. Additionally, a multifunctional radar developed by the research group (as shown in Figure 7) is used as a third reference radar.

In 2019, the UK company AVEILLANT launched the C-UAS solution Eagle-SHIELD for protecting sensitive civilian facilities. The radar uses the Gamekeeper radar, a holographic radar system, with 4×16 receiving channels, operating in the L-band, a PRF of 18 kHz, a range resolution of 75 m, a pitch angle range of 30°, and a data update duration of 0.25 s, with a detection range of 5 km for drones with a typical RCS of 0.01 m2. In 2022, the French company Thales demonstrated a new generation C-UAS solution Horus-Shield under the Eagle-SHIELD framework. The radar is the SQUIRE radar, operating in the X-band with FMCW, and has a detection range of 3 km for drones with a typical RCS of 0.01 m2. Since 2020, the ATR research group at Wuhan University, in collaboration with partners, has developed a new generation multifunctional intelligent radar solution WHU-X001. This radar operates in the X-band, has a coherent processing interval of about 20 ms and a pulse repetition frequency of 5 kHz. The transmission bandwidth is about 12.5 MHz, providing a range resolution of about 12 m. The radar system is equipped with an Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) antenna and is mounted on a rotating table for 360° azimuth scanning coverage. With the fully programmable software capabilities, it has real-time ATR recognition capabilities and can identify drones with a typical RCS of 0.01 m2 at a detection range of 12 km. This radar solution can be used in fields such as airport bird detection radar, anti-drone radar, and coastal surveillance radar.

The traditional radar signal processing flow typically includes signal detection, target tracking, and target identification units. The signal processing flow is presented in a serial, unidirectional manner: first, signal detection is performed to detect the echo signal, which is then passed to the target tracking unit, and finally enters the identification unit for target recognition.

4.1 Detection Range

The detection range is generally considered an indicator of the radar signal detection capability and is one of the most important radar performance parameters. The radar equation assumes that the target can be viewed as a point target with an average radar cross-section. This equation can calculate the SNR, which is used to measure the radar system's ability to detect specific targets within a certain range by comparing the target's scattering power with the background noise. The mathematical expression of the radar equation is as follows:

Where: Ts is the system noise temperature, Bn is the receiver's noise bandwidth, L is the total system loss, k is the Boltzmann constant, Pt is the transmission power, Gr is the receiving gain, Gt is the transmitting gain, R is the measurement range, σ is the target's radar cross-section, and λ is the radar wavelength. The radar equation illustrates that the basic principle of radar design is the principle of radar detection. For single pulse detection, if the detection probability exceeds 50%, the target's SNR should be at least 13.1 dB. To achieve a 95% detection probability, the SNR should be 16.8 dB. In simple terms, smaller targets with lower radar RCS will have lower SNR, resulting in a reduced detection range. Therefore, radar systems often face challenges of 'missed detection' and 'false alarms' when detecting drones and other objects with smaller radar RCS.

Regarding distance, the 'track radar' (as shown in Figure 7(a)) uses the L-band to detect drone targets, possibly considering the use of resonance effects to enhance the energy of the drone echo signals. Theoretically, the L-band radar is roughly similar in size to the drone targets (Group 1 & 2 in Table 2), thus the echoes are in the resonance region. Due to the energy amplification effect of resonance, the RCS of the drone is amplified. Compared to X-band radar, the echo signals received by L-band radar have a higher SNR, potentially exceeding 20 dB. This design can significantly increase the detection range of drone targets. Additionally, the ATR method based on track discrimination actually involves two main issues: 1) how to detect weak signals; 2) how to perform track association. In the resonance region, the RCS of the drone is amplified, so its echo signal is no longer weak. When the trajectory of the drone echo can be stably and quickly plotted, it also aids in track association, ultimately assisting in target tracking, and using track discrimination also helps in target identification.

However, the track discrimination scheme also has some drawbacks. First, the 'track radar' system is costly and requires precise measurement of target coordinates. To this end, the 'track radar' employs a Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO) scheme and requires continuous tracking status for detection. Therefore, this radar is also referred to as 'staring radar', which actually maintains a fixed azimuth angle for continuous scanning and tracking of the target (as shown in Figure 9(a)). It is claimed that this can measure the three-dimensional position of the target with high precision and is used for target identification. Secondly, many interfering targets, especially birds, can also cause an increase in RCS due to resonance effects, thereby interfering with the detection of drone echoes. Since the trajectories of birds often overlap with those of drones, the robustness of track discrimination still needs improvement. Furthermore, compared to the X-band (optical region band), the wavelength of the L-band is about ten times larger, and under the same conditions, its Doppler resolution is roughly 1/10 that of X-band radar. Poor frequency resolution is not conducive to detecting features such as micro-Doppler signals, nor is it favorable for identifying multi-dimensional features (such as combined micro-Doppler, tracks, etc.). Finally, track discrimination is still limited by detection range; when the drone is far away, its echo energy remains very low, which may lead to false alarms, and considering the slow flight speed of drones, it is also difficult to cross distance units. This makes it challenging to stably track drones at long distances and even more difficult to perform target identification.

Stay tuned for more exciting content in the next issue...

*Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the author and is only for academic sharing, not representing any stance. If there is any infringement or objection, please contact the editor for deletion.